NANOGrav 15-yr and Massive Gravity

reproducing the SGWB with massive gravity

This post summarizes the paper I wrote with Jacob Magallanes, Murman Gurgenidze, and Tina Kahniashvili. The code for the paper is available here and the TeX is available here.

Content of this post is a work in progress!

Background

On June 28th, 2023, the NANOGrav collaboration published a series of papers (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6) on the detection of a stochastic gravitational wave background (SGWB) with a pulsar timing array (PTA) and its implications and methods.

At around the same time, I, along with Jacob Magallanes and Murman Gurgenidze, was tasked by Prof. Tina Kahniashvili to reproduce the results of Fujita et al. 2018 and Gumrukcuoglu et al. 2012, in our efforts to eventually connect it with the NANOGrav results. The two papers detailed the observational prospects of the minimal theory of massive gravity (MTMG) with different time-dependencies of the graviton mass. We had spent the majority of the summer to this end, and it wasn’t until mid-October that I had finally reproduced the significant results from the two papers that we were ready to move on.

Prof. Kahniashvili had originally intended to use the NANOGrav 15 yr data (which we will refer to as NG15 to match our paper) to constrain the graviton mass, but to our surprise, two papers had already been published that did exactly this with the NANOGrav 15 yr results, Wang et al. 2023, Wu et al. 2023. We shifted our attention to the time-dependent model of MTMG, something no one had previously tried to connect with NG15. And thus, on October 17, 2023 at precisely 21:33 EST, I began writing the paper that we wanted to put out as soon as we could.

Gravitational Wave Background

What is a gravitational wave background? To even address this question, we must build up our intuition of gravitational waves. Gravity, one of the fundamental forces of nature that may or may not have a quantum field theoretic description, acts on any massive or energetic body. In order for the gravitational field to update with changes in the mass and energy distribution within spacetime, the information must be carried via some sort of messenger, much like in the case of the electromagnetic (EM) field. Whereas photons/EM waves are what update the EM field, gravitons/gravitational waves (GWs) update the gravitational field.

Gravitational Waves

GWs are produced by accelerating mass/energy distributions, much like how light is produced by accelerating charges. They are ripples in spacetime, allowing for two modes of polarization, the “plus” (+) and “cross” modes (\(\times\))

GW waves propogating by stretching and squeezing spacetime itself in perpendicular directions. There are three general categories of polarizations: scalar, vector, and tensor polarizations. They differ in the way they distort the spacetime and the direction they are allowed to propogate. According to GR, only tensor perturbations, of which there are two, can exist and the other modes are forbidden. Any observation that detects other modes would show that there more to gravity than GR.

First Detection

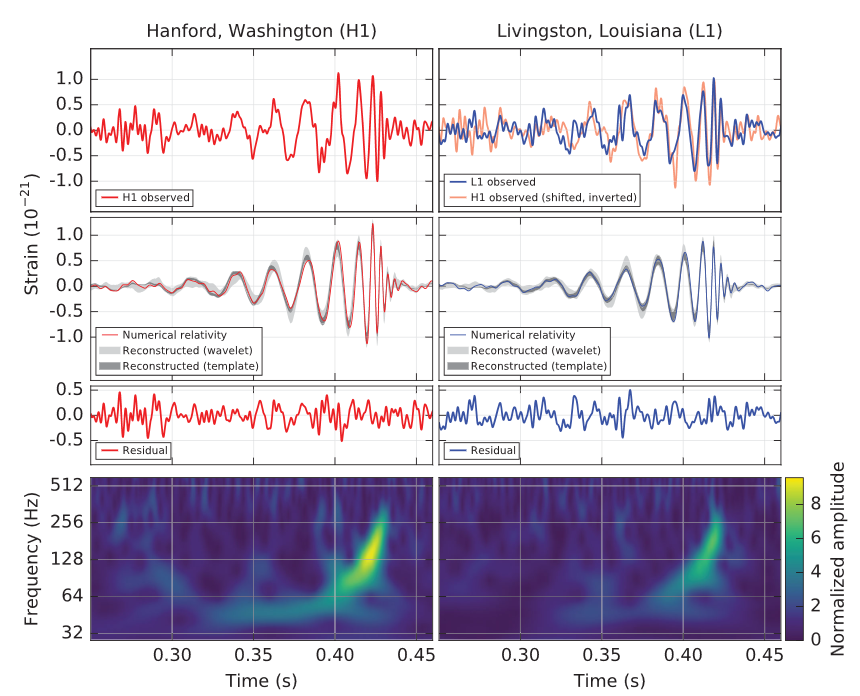

GWs were first detected in September 14, 2015, almost exactly a century after they were first predicted by Albert Einstein in 1916 through his theory of general relativity (GR), by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) detectors at Hanford, Washington and Livingston, Louisiana. These detectors have two 4 km arms arranged perpendicularly to each other and they use laser interferometry to detect changes in distances in spacetime to less than \(10^{-5}\) of the width of a proton.

The detected GWs were generated from a binary black hole merger (Abbott et al. 2016), and since then, nearly a hundred GW events from black hole and neutron star mergers have been detected by the combined efforts of LIGO, Virgo, and KAGRA, the Italian and Japanese counterparts of LIGO respectively. Currently, the detectors have paused their run, and are under maintenance to improve the sensitivities, aiming to achieve observations of GWs every other day.

NANOGrav

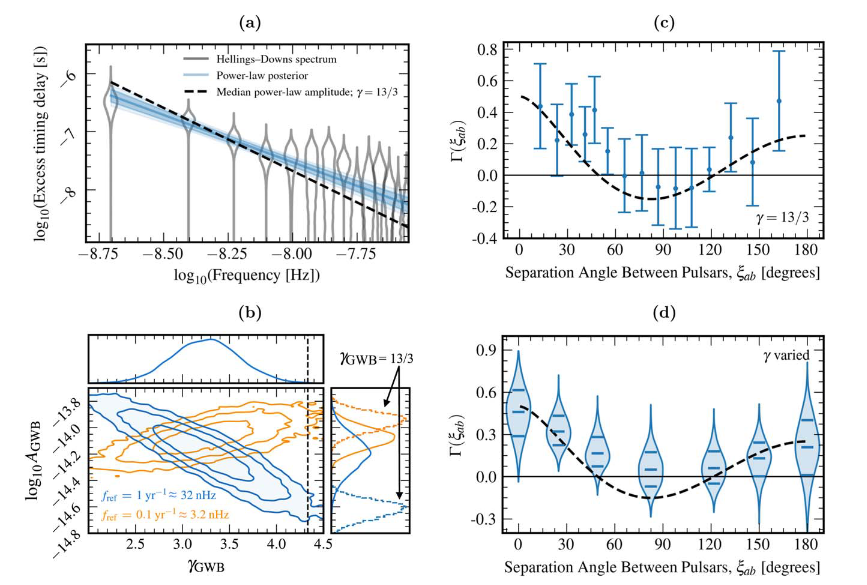

So clearly, gravitational wave physics seems to be popping off. Where does NANOGrav fit in all of this? There was a proposal to use millisecond pulsars as a way of detecting GWs. They have extremely regular periods, and so can be treated as the ends of a galaxy-sized interferometer arm. An array of these pulsars would be able to detect very low-frequency gravitational waves, since the GWs perturbing these pulsars would have to have wavelengths on that scale. In 1983, Hellings and Downs predicted that a SGWB (stochastic because it would be caused by a random process) would produce a distinctive GW signature, specifically that of a quadrupole spatial correlation (Hellings et al. 1983)

The NANOGrav collaboration has been collecting data from pulsars within our galaxy (about 67 pulsars in total) since 2005. In June 2023, they summarized the results from the 15-year data release (we refer to this as NG15 to match our paper) in the paper Agazie et al. 2023.

They give strong evidence for the detection of a SGWB for the first time, and this prompted researchers to provide an explanation for the background. The most commonly held source is inspiraling supermassive black hole binaries (SBHBs), which emit low-frequency gravitational radiation through their orbits. We think that the closest, most massive binaries emit continuous GWs which would lead to the dominant portion of the SGWB. However, there is most likely more to the story, since that expanation doesn’t entirely describe the signal we observe.

New Physics Sources

Many different possible explanations that aren’t astrophysical in origin are proposed, summarized in the second paragraph of the introduction of my paper. To briefly recount, possible explanations, with the references suppressed since they are already enumerated in the paper, are cosmic strings, domain walls, first-order phase transitions in the early universe, primordial magnetic fields, primordial GWs, scalar-induced GWs generated by primordial black holes, and even a non-GW explanation for the background. These exhibit varying backgrounds in the frequency range of the observation, but they all can reproduce the signal to some extent.

Due to our work with massive gravity, and considering the lack of literature that primarily uses massive gravity to explain the signal, we use it in conjunction with primordial GWs to explain NG15.

Massive Gravity

Gravitational waves, and gravitons by extension, are typically thought of as massless, much like the photon. However, this doesn’t necessarily have to be true. If we allow the graviton to have a non-zero positive mass, then interesting behavior of the field emerge. Firstly, we note that any linear theory of MG suffers from the vDVZ discontinuity, ghost instabilities, and other issues. Many attempts have been made to address this and extend it to a non-linear theory. One successful way was done by the deRham-Gabadadze-Tolley (dRGT) theory, by introducing polynomial interaction terms with arbitrary coefficients. We use a similar approach, one originally laid out by De Felice et al. 2015. This version of the theory is called the minimal theory of massive gravity (MTMG) and it is an extension of dRGT.

Our quadratic action is defined as (Eq. 4 of Choi et al. 2023)

\[S = \frac{M_{\text{Pl}}^2}{8}\int d^4xNa^3\left[ \frac{h'^2_{ij}}{N^2}- \frac{(\partial h_{ij})^2}{a^2} - M_{\text{GW}}^2h_{ij}^2 \right] ,\]where \(M_{\text{Pl}}\) is the Planck mass, \(h_{ij}\) is the spatial part of the perturbation of the metric \(g_{\mu\nu}\) defined by \(g_{\mu\nu} = \eta_{\mu\nu} + h_{\mu\nu}\), \(N(t)\) is the lapse function, \(a(t)\) is the scale factor, and we defined \(M_{\text{GW}}(t)\) as the mass of the graviton. From this, we can derive the equation of motion for the tensor perturbations, i.e. the gravitational waves. By decomposing the tensor perturbations into the + and \(\times\) polarizations, and suppressing them as their equations of motions are identical, we get the following form for our equation of motion (Eq. 7 of Choi et al. 2023)

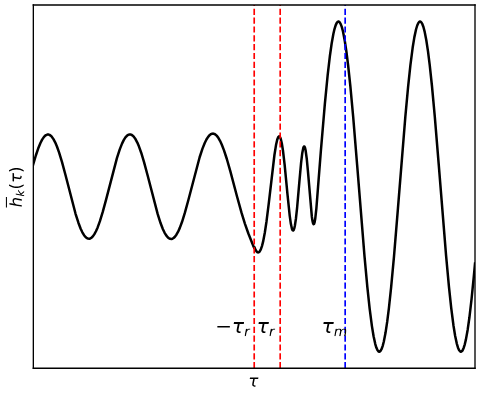

\[\bar{h}_k'' + \left(k^2 + a^2 M_\text{GW}^2 - \frac{a''}{a}\right)\bar{h}_k = 0 \ ,\]where \(k\) is the comoving momentum of the gravitational waves and the primes (‘) are with respect to the conformal time defined by \(\tau = \int \frac{Ndt}{a}\) where \(t\) is the proper time we are familiar with. In order to solve this equation, whose solution we will need for later, we need to define the behavior of \(a(\tau)\) and \(M_{\text{GW}}(\tau)\).

The scale factor can be described by the following equation

\[a(\tau) = \begin{cases} -1/(H_{\inf}\tau) & \tau < \tau_r \\ a_r \tau/\tau_r & \tau > \tau_r \\ \end{cases}\]Here, \(a_r\) is the scale factor at the reheating time \(\tau_r = 1/(a_r H_{\text{inf}})\). We assume \(a_r\) is fixed in this paper and that \(H_{\text{inf}}\) and \(\tau_r\) may vary. We tried to vary \(a_r\) at first, but it didn’t seem logical to fix the cutoff time but not the scale factor of inflation, which seems like more a constant of nature. Fujita et al. 2018 assumes a step-function behavior for \(M_{\text{GW}}\), defined in the following way

\[M_\text{GW}(\tau) = \begin{cases} m & \tau < \tau_m \\ 0 & \tau > \tau_m \end{cases}\]where \(\tau_m\) is the conformal time when the graviton mass instantaneously drops to 0. This is obviously an unphysical model, but it is a very simple toy model for time dependence that we can use to start to understand what sorts of behaviors to expect. The actual dependence on time maybe be approximated to be a step function, so it is not a totally unrealistic ansatz to start with.

The solution to the equation of motion has the following behavior:

We see that it always has a sinusoidal behavior, and has a constant amplitude during the inflation phase and during the massless phase. During the mass dominant phase, it has a decaying mode, but its decay is slower compared to the massless graviton’s mode decay, and so its final amplitude should be amplified or blue tilted compared to the massless graviton. Explicit expressions (in the superhorizon and subhorizon limits) for each phase of the mode function can be found in Sec. III of Fujita et al. 2018.

Energy Spectrum

Firstly, we want to see if there’s any relvant quantity related to gravitational waves to look at. Luckily, there is such a quantity that is widely studied, specifically the energy density spectrum at the present time. This is a practical way that allows us to determine the influence of deviations of GR on the gravitational waves generated from inflation. There are various other quantities one could look at, like the power spectral density, characteristic strain, the amplitude of the gravitational waves, and many more. These quantities are all usually related to each other, with some constant factor multiplied by the frequency raised to another constant factor.

The energy density is defined as

\[\Omega_{\text{GW}} = \frac{1}{\rho_c}\frac{d\rho_{\text{GW}}}{d\log k}\]where \(\rho_c = 3H^2/8\pi G\) is the critical density, and we note that \(\frac{d\rho_{\text{GW}}}{d\log k}\) is a notational way of representing the spectral density of \(\rho_\text{GW}\) rather than a literal derivative with respect to \(\log k\) (see Footnote 65 of Maggiore et al. 2007).

We can connect this with the energy density per logarithmic interval of wavenumber via the expression (Eq. 17 in our paper):

\[\Omega_{\text{GW}}(\tau,k) = \frac{1}{12} \left( \frac{k}{aH} \right)^2 \mathcal{P}_h(\tau,k),\]where \((\mathcal{P}_h(\tau,k))\) is the tensor power spectrum, defined as:

\[\mathcal{P}_h(\tau,k) = \frac{k^3}{\pi^2} \left|\bar{h}_k(\tau)\right|^2.\]This equation shows explicitly that the behavior of the mode function \(\bar{h}_k\) encodes all the information about how the mass of the graviton affects the observed spectrum today. The energy density spectrum is particularly useful because it can be directly compared to observational limits or detections of a stochastic background like those reported by NANOGrav. I believe most of the analysis done by researchers related to PTAs are actually on the energy density spectrum, or power spectrum, rather than the angular correlation from the overlap reduction function. There are subtle differences between the these various quantities, like energy density, power spectrum, power spectral density, the characteristic strain, etc. See Moore 2014 [1408.0740] for a very nice discussion of how all of these are related. Eq. 29 is especially useful.

In our work, we numerically solved the equation of motion for \(\bar{h}_k(\tau)\) over a wide range of comoving momenta \(k\), using the step-function mass model described earlier. In particular, we used the approximation of the transfer function from Kuroyanagi et al. 2014 [1407.4785]. We then computed the corresponding energy density spectrum \(\Omega_{\text{GW}}(f)\) evaluated today, where \(f\) is the present-day frequency related to the comoving wavenumber by the usual redshifting relation:

\[f = \frac{k}{2\pi a_0},\]with \(a_0 = 1\).

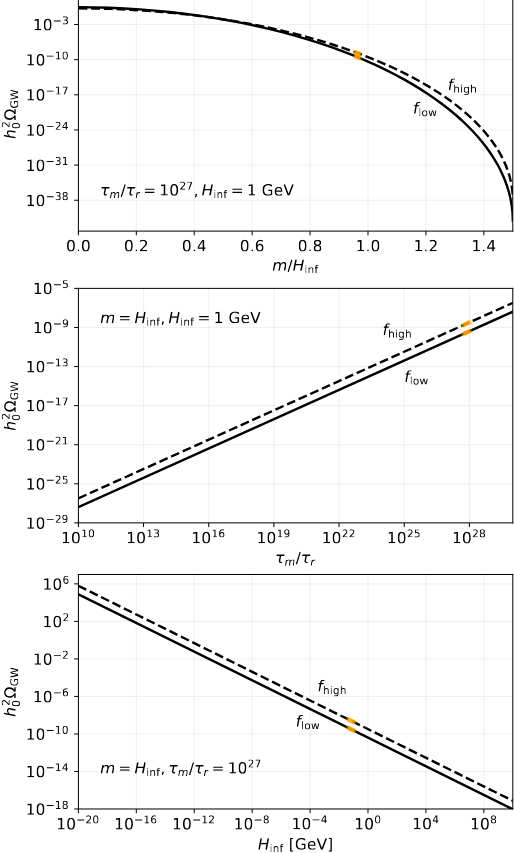

For the subsequent analysis, we would like to know how this spectrum varies with different parameters. We plot the energy density as a function of the the model parameters:

- the graviton mass during the massive phase (\(m\)),

- the time when the mass decays to zero (\(\tau_m\)),

- and the inflationary Hubble parameter (\(H_{\text{inf}}\)).

It looks something like this: (reproduced from Figure 2 of our paper):

When the graviton is temporarily massive during inflation or reheating, the resulting spectrum can be strongly blue-tilted, meaning that the amplitude increases with frequency. This is in contrast to the nearly scale-invariant (flat) primordial spectrum from massless tensor perturbations in standard inflationary scenarios. The blue-tilted terminology simply comes from the analogous notion of frequencies being blue-shifted because of the Doppler effect.

Connecting to NANOGrav

Once we computed the spectrum, we needed to see if it could explain the signal detected by NANOGrav. Recall that the NANOGrav measurement is typically expressed in terms of the characteristic strain spectrum, which is related to \(\Omega_{\text{GW}}\) by:

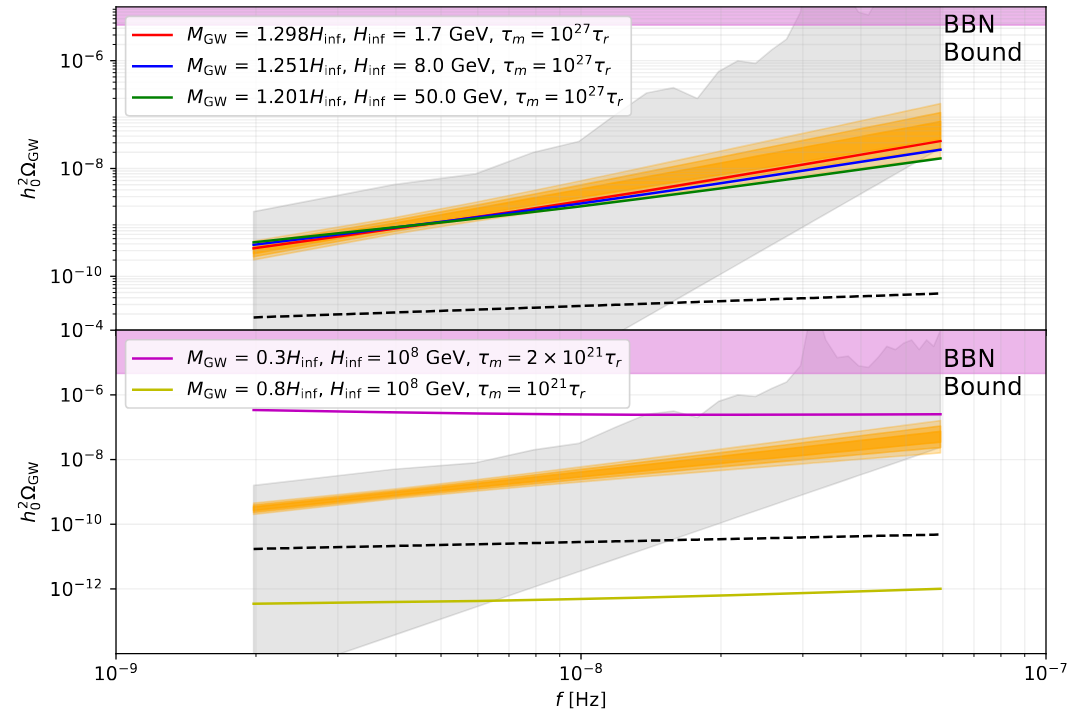

\[h_c(f) = \sqrt{\frac{3H_0^2}{2\pi^2}} \frac{\Omega_{\text{GW}}(f)^{1/2}}{f},\]where \(H_0\) is the present-day Hubble parameter. We converted our results into this form and overlaid them on the NANOGrav posterior for the energy density, as seen in the next figure:

Results

Our main findings can be summarized as follows:

- The time-dependent massive graviton scenario predicts a blue-tilted spectrum that can naturally match the higher-frequency rise in the NANOGrav data.

- The model provides a good fit without requiring unrealistically large tensor-to-scalar ratios, staying within bounds imposed by the CMB.

- Compared to a purely massless primordial gravitational wave background, the time-dependent mass scenario improves the fit to the NANOGrav data.

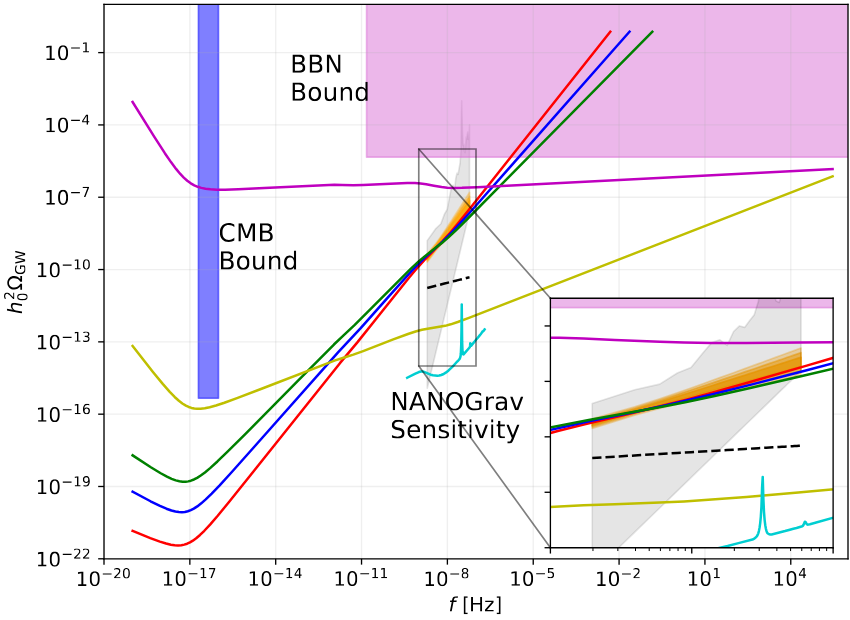

Respect of the different constraints is summarized in the next figure.

Our work shows that time-dependent massive gravity is a viable alternative to astrophysical sources of the SGWBs, but if the gravitational waves were massive when big bang nucleosynthesis takes place, then it turns out that we do not need to respect the BBN bound. However, the CMB bound must still be respected, which our energy densities do.

Outlook

Going forward, there are several directions that could extend this analysis. While our model used a simple step function for \(M_{\text{GW}}(\tau)\), a more realistic scenario would include a smooth decay or a parametrically varying mass. We did not have the time in this paper to explore this, but it would be worth investigating. Future studies could jointly analyze NANOGrav, EPTA, PPTA, CPTA, and IPTA datasets to improve constraints. CPTA claims frequency-dependence in their data, so we may possibly use this to constrain the parameters even more. If the GWs aren’t massive during BBN, then it must respect the BBN bounds. Three of the energy densities we looked at, the red, blue, and green ones in the last figure, all have their energy densities violating the BBN bound for higher frequencies. This must mean that these modes are suppressed by some mechanism. It could perhaps be due to anisotropic stress perhaps from free-neutrinos, like it was explored in a paper by Weinberg, 2003 [0306304] and my advisor Kahniashvili et al. 1997 [9702226].

With ever improving observational prospects and improved sensitivies in the power spectra, like in the Square Kilometer Array (SKA) or even LISA, we may soon be able to tell whether signatures of massive gravity are hidden in the stochastic gravitational wave background.