How I prepared for my Qualifying exam (and what actually worked).

I recently took my oral qualifying exam in my PhD physics program, and I passed!

This post is my attempt to write down exactly what I did to prepare, what actually mattered, what didn’t, and what I would do differently if I had to repeat the process. I’m writing this partly for future students and partly for my future self, because it’s easy to forget the minute details of how it went.

Context: what the exam is (at CMU)

In Carnegie Mellon’s Physics PhD program, we take an oral qualifying exam in our second year (typically about a week before classes begin). The exam is a committee-style oral where you present a short talk about your research for about 30 minutes, and then answer questions from three oral committee members about the presentation. For me, my presentation was on Jan. 8th, 2026 at 12:00 PM and the writeup was due on Dec. 22nd, 2025.

The writeup is a paper that you submit a couple weeks before the actual presentation, so that they have a document they can look at beforehand to come up with questions. The content on the writeup and on the presentation should be pretty similar, without anything completely different showing up. I started the writeup about 4 days before it was due, which I believe was more than enough time to finish it to my satisfaction. Earlier that year, I had a very basic draft of it, that I created by simply appending my two papers togther. The only issue was that the maximum page limit was about 6 pages, according to the rubric, but my draft was already at like 36 pages, so I realized I had to actually put in the effort to make it concise.

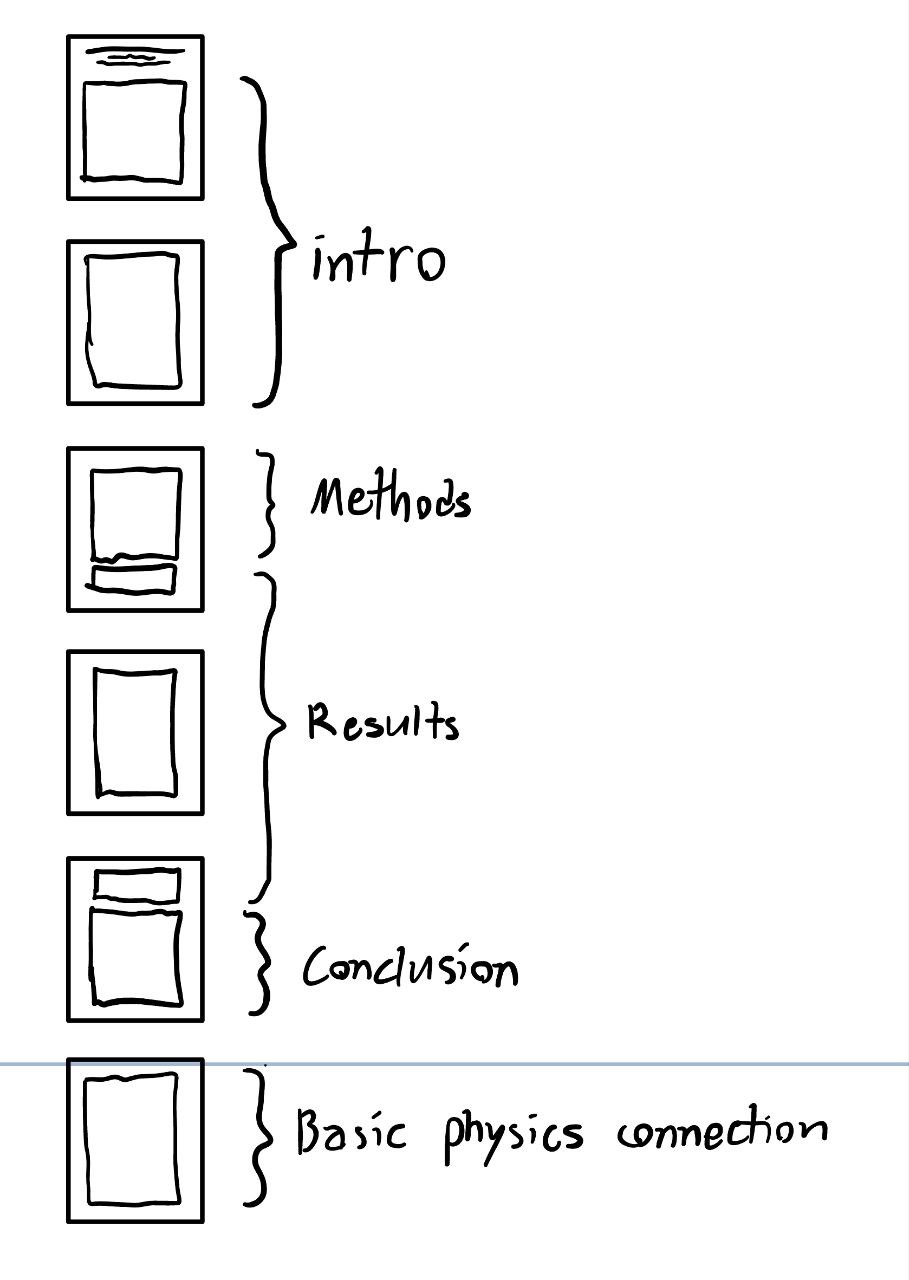

The writeup is split into roughly five sections:

- Introduction and Motivation: (up to 2 pages)

- Methods and Approach: (up to 1 page)

- Status and Results: (up to 2 pages)

- Conclusions and Next Steps: (up to 1 page)

- Basic Physics connections: (at least 1 page)

Adding these up yields 7 pages, but the rubric suggested a maximum limit of 6 pages, with the figures/tables and references not counting towards the total count. My idea of how I can apportion the parts into the pages was with this visual.

My goal here was to summarize these two papers that I had wrote over the last 2 years, and do it in such a way that would make sense. My first project focused on the energy density of inflationary gravitational waves, modified by massive gravity, and my second project focused on the overlap reduction function, modified by massive gravity. Both were in the context of pulsar timing arrays (PTAs), so in a sense, they were both sides of the same coin. What I ended up doing was splitting the Methods and Results sections in 2 parts, each, where I focused on what I did and got for each of the two papers individually. This was the best way I could think of to coherently explain my work that tackled two different aspects of the same PTA data.

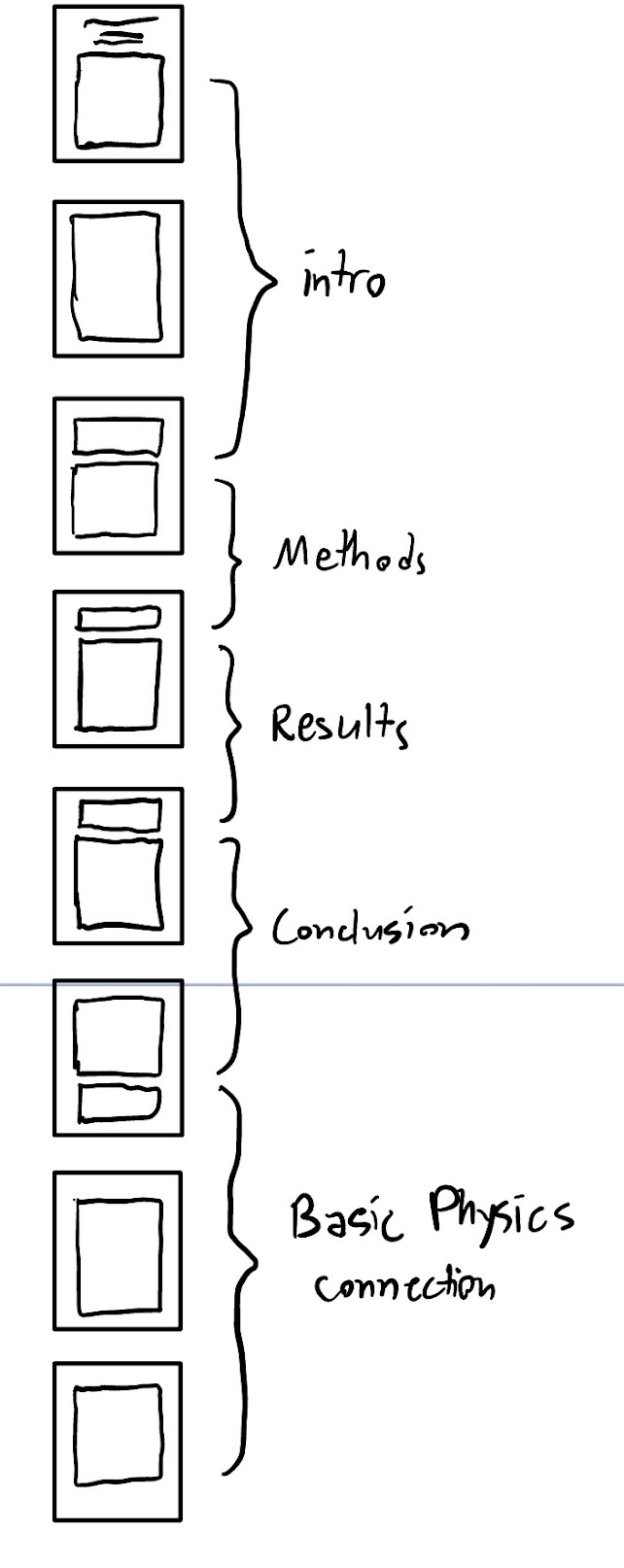

My actual writeup ended up having the following structure

I was very pleased with how it came out, and I submitted it around 10 hours before it was due. Yes, my final writeup ended up being a lot longer than what they wanted, and with the figures and references, it ended up being around 16 pages (I had 132 references in total!), but I figured that I cut out as much as I could. And because they didn’t return it to me to shorten, I figure that it was acceptable. My advice is, don’t worry too much about the page constraints, as long as it isn’t unreasonable (within 1-2 pages of the limit) and you hit every point you want to, it is good enough. Much of my presentation would be based on the content I mentioned in the paper, but I knew the hard work was still ahead; I still had to fill in the details of the slides.

My slides were structured in the following way

- Research portion: with recommended time of 20 minutes

- Basic physics connection portion: with recommended time of 10 minutes

This was what the rubric required us to split the talk into, but within each section, you have complete freedom with what you choose to include, as well as where you want the basic physics connections to go (perhaps in the intro when you are deriving your theory, or at the end, to make it simple for time-keeping). I personally put it at the very end.

Here is roughly how my quals went:

Examiner A

Examiner A: So why massive gravity? you know, there are a lot more parameters it is introducing compared to GR, so why introduce all of it, what is it solving exactly?

Me: There are a lot of open problems in cosmology, including the tension of the hubble parameter and sigma 8 tension, as well as not having a quantum gravity yet, as well as us not knowing exactly what dark energy and dark matter are. massive gravity provides quite an elegant explanation for two of these problems. I believe that it is able to more convincingly solve the dark energy than the dark matter, since multiple field excitations of spin 2 are needed, since the lower bound on the DM mass and the upper bound on the graviton mass do not overlap, so it is a bit more tricky and involved to explain DM than DE in my opinion

u go more into detail for this, how can you do this, what is the form of the stress energy tensor would you need?

Me: sure, here is my backup slide on this. We see that massive gravity provides exactly the right form of the stress energy tensor that we need, and its scale is set by the mass of the graviton itself.

Examiner A: so the scale of expansion is set by the mass? how does that work? does this provide bounds on the mass

Me: right, we know that the dark energy constant is extremely small, so that would imply a very small mass, and we have bounds from this

Examiner A: ok, so now talk to me about this discontinuity you mention, the vDVZ discontinuity. how is it solved?

Me: this is the van dam veltman zakharov discontinuity which states that as you take the limit of the mass going to 0, the scalar modes do not go away. The Vainshtein mechanism is introduced and effectively screens out the modes within a Vainshtein radius

Examiner A: what exactly is this radius? what is going on with the scalar modes within this radius?

Me: so this radius is sets the scale for which the scalar modes do not exist, and outside of which we do have scalar modes.

Examiner A: Can you talk more about how in the minimal theory of massive gravity, there is a breaking of the lorentz invariance. does that mean there is a preferred frame now? Why the lorentz invariance breaking

Me: In the theory, the only way to get the 2 propagating tensor degrees of freedom is to break lorentz invariance on the global scale, not a spontaneous symmetry breaking, and i guess that is what that would mean, a preferred frame, but im not really sure. We see that there are multiple theories here that break lorentz invariance, so im not sure what it would it imply about that.

Examiner A: can you tell me more about these pulsar terms in the exponential, where do they come from?

| Me: So they come from essentially taking the difference between the characteristic strain of the GW mode at the pulsar and at earth, well in reality it is the solar system barycenter. But this makes it so that at the earth, we have that the whole exponent goes to 1 since we are located at 0 distance, but then for the pulsars, we get a non 0 term in the phase. here we have this term $1 + \frac{ | k | }{k_0} \Omega\cdot\hat{p}$ which essentially comes from inputting the retarded time into the characteristic strain. |

Examiner A: ok that makes sense. can you tell us more about BBN how it gives us this bound

Me: yes, i have a slide on that. de just for this. So in essence, we have these very good observations of the abundances of the light element, you know, such as helium 4 or deuterium. In order to not mess up observations, we have to constrain the energy density of relativistic species. See this term here , the $\rho_{extra}$ , this is what you get when you start to consider gravitational waves. So we formulate the constraint as a difference between the N_eff and what value we expect without considering gravitons, about 3.043 or something like that. Oh and lastly, this is sensitive to the ratio of the number density of neutrons to protons, since they freeze out at some point.

Examiner A: can you tell us more about this blue tilt? How does it appear

Me: yes, this blue tilt is something we get from the transfer function, which is fitted, and then it multiplies the power spectrum from GR

Examiner A: Could you tell us more about how the damping could happen, you mentioned the neutrinos free streaming, how would this cause the damping to occur.

Me: yeah, so basically the damping is something that might be caused not within the massive gravity itself.But something external, such as the neutrino free streaming that I mentioned so essentially, in the early universe, the neutrinos decouple from the out of equilibrium.And they become free streaming.And this includes a damping term.I believe in the einstein field.Equation on the right side, the stress energy tensor it has a non zero component.So that contributes a sort of damping on the oscillating modes

Examiner A: um, do you know what?This is called the actual terms within the stress energy tensor I’ll give you a hint.It starts with a v

Me: yeah, I actually, i’m not able to think of it at the moment

Examiner A: it’s called the viscosity

Examiner B

Examiner B: I am wondering, what is a pulsar?

Me: a pulsar is essentially a neutron star, which has an axis of rotation at a specific orientation, and itll have a magnetic field, which will be aligned in a different direction, and its essentially going to precess and when the magnetic field intersects with us here on earth, itll be detected and that is what we call a pulsar.

Examiner B: anything else? How does the line of sight mean it is a pulsar?

Me: well, I guess that its going to only intersect our line of sight every time it revolves, so once every period. This is what we are detecting. The pulsars axis of rotation and magnetic field are always misaligned, so we will always detect these as pulses periodically. I guess in the astronomically low chance that these two align, we would be detecting constant emissions but this is not possible usually.

Examiner B: and could you tell me how neutron stars are formed?

Me: Yes, pulsars are essentially formed when we have a very massive star near the end of its life, you know, itll have formed the heavy elements which all go to the center, and itll go through a supernova, and itll shed some energy from radiation and from neutrinos, and then itll undergo a gravitational collapse, in which it will become a neutron star. If the mass of the star is higher, then itll keep going in its gravitational collapse and itll form a black hole instead.

Examiner B: does the period of the neutron star get worse over time, does this cause any issues with trying to measure the signal?

Me: yes, allow me to drive a board here. So, this is essentially a graph of the derivative of the peered, with respect to time Vs the period of the neutron star. And we see on here, I’m driving the death line, which is past this point. There aren’t there can’t be any neutron star formation. So real second, pulsar is the ones that we use in this experiment are located right here in this lower left region. So as you can see, it’s a very low period it’s decay of its spirit is very low which sets a time. So that makes an ideal candidate for trying to measure the just to measure the signals for this for this observation here, I’m also going to draw how the English frequency drops off over time. Here it is increasing, oh wait, no, no, no. Let me think about it. I guess there’ll be yeah. It’ll be decreasing. The frequency would be decreasing with time, and yeah, that sense. So sometimes, what happens is that there’s like, a little glitch, a little kind of discontinuous jump that happens like, maybe this happens, like once every 50 to a 100 years, for some plus ours, it doesn’t have. We haven’t observed it at all, but for others it happens, you know, a bit more frequently like, you know, 3 times per century. And so this essentially makes it so that if it happens too often, then the art timing model of this pulsar is not as accurate. So we actually have to throw away the pulsars from our collection of ones that are working at that in order to improve the noise and the signal to noise ratio

Examiner B: what is the difference between a neutron star and black hole?

Me: The main difference between the two is that a black hole has a radius for which nothing can escape, whereas a neutron star wont have this region and if you are going fast enough, you would be able to escape from it.

Examiner B: What is this radius exactly, can you tell me more about it?

Me: Yes, this radius is called a Schwarzschild radius, and it is dependent on the mass i guess. It is essentially the size of the black hole. In actual black holes, because we have kerr black holes that have an angular momentum, they will be more like a ring, and itll be called an ergosphere.

Examiner B: what does this radius depend on?

Me: It depends on the mass of the black hole, i suppose. itll also depend on the gravitational constant G. I think thats it, right?

Examiner B: I believe there is also a factor 2, and a $c^2$ in there somewhere.

Examiner C: $c = 1$, haha. Im only joking

Me: ok

Examiner B: so on slide 15, you show us fits to the data. I would like to know how you generated these fits.

Me: Yes, so we used a single parameter, the group velocity in this case, and we did a simple chi-squared fitting to the binned values, since CPTA unfortunately doesnt make the data public so the binned correlations are all we have. We then generate the plots, doing the full chi squared fitting

Examiner B: you did the fitting your

Examiner B: I saw you mention something called a Hankel function. i know of bessel functions, but i have never heard of this. can you explain this?

Me: Yes, allow me to write on the board. Now, I said that in the presentation that we do not generically know the form of the mode equation, but in the case of a simple step function of mass dependence with time and the era of inflation, i believe, we are able to solve it analytically. We have that the mode equation is of this form

\(\bar{h}_{k}'' + \left( k^{2} + \frac{1}{\tau^{2}}(\dots) \right)\bar{h}_{k} = 0\)

where there is some constant inside the parantheses there. We can multiply both sides by $\tau^{2}$ and we get the exact form for a differential equation whos solution is the Hankel function. The Hankel function is essentially the complex version of a Bessel function, and its index $\nu$ will be set by what i show in the slides.

Examiner B: Now, i want to go back to the clebsch gordan stuff. so i am a particle physicist and we have these things called mesons which are what happens when you combine a quark and an anti-quark.

Firstly, what are the allowed total angular momentum from this system?

| Me: We have that the total angular momentum $J$ is bounded from above by $j_{1} + j_{2}$ which is 1 in this case, and bounded from below by $ | j_{1} - j_{2} | $ which is 0 in this case, since the spin of quarks are 1/2. I believe there would be 2 states for this |

Examiner B: Well, are you sure about that?

| Me: oh wait, no, we have the three states of $J=1$ and a single state of $ | 0,0\rangle$ so i guess we would have 4 states. |

Examiner B: Good. How would the Clebsch gordan coefficients look like for this system? I know you calculated it already for your case, but can you tell us how you would do it for this.

| Me: Yes, we would essentially do the same thing, but we would start with the highest weight state for this, which would be the $ | 1,1\rangle$ state, and then do the lowering procedure from there. |

Examiner B: yes, that is all for me

Examiner C

Examiner C: so you know i work with black holes and simulations of them a lot, so i have some questions for you about that. How would massive gravity, you know, for either formulation you work with, affect the GW signature from black holes?

Me: We have so we have that the black holes that were dead are obviously consumer, massive black holes, but we have witnessed an ensemble of them. And they’re going to be, you know, under order of at least millions or billions of lightyears away. And the ones that are closest to us, the ones that are more dominant, they’re dominate the signal. But yeah, we don’t expect quite a smooth dependence of the power law

Examiner C: i want to ask you about the frequency. So these black holes, they’re quite massive, aren’t they? Will the frequency depend on the mass of these black holes, or what

Me: that’s a good question. Lemme think about that, yeah, I don’t think the frequency would depend on the mass

Examiner C: Oh they very much do

Me: Oh wait, they do? oh I didn’t know that okay. I’ll keep that in mind

Examiner C: How do the black hole simulations inform you about the background?

Me: We know from simulations that we have a power law with a spectral index of 13/3 from supermassive black hole binaries. We may find out that there is a more complicated frequency dependence, this would show up as a change in the actual shape of the energy density spectrum as a function of frequency.

End of what I can remember.

I do remember the Examiner C going on for quite a bit longer, but for the life of me, I could not recall the questions. Just a lot more based on the black hole stuff.

Anyway, I learned a lot from this experience.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: